Reflet dans un diamant mort

Without light there is no image. Within the reflections of a diamond, there are many. Trapped and multiplied. Refracted and dispersed. Breaking light into its primary components. Outing bows without rain. Stormless rainbows. Diamonds bear the capacity of showing the core of light. Which is why not only the greedy love them, but so do those who love images. Or should we say that those who love images are the greediest? “Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see”1 Renée Magritte in a radio interview with Jean Neyens (1965), cited in Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, trans. Richard Millen (New York: Harry N. Abrams), p. 172.. Image-lovers never get enough of them. Until they’re encouraged by night’s darkness to close their eyes and go to sleep. And even then, they dream of images. They fight against the void, the starless night, the nothingness. Most of us are image-lovers, living in the world of appearances, greedy for light, always more light. 24/7 litten neon signs. Screens flickering between our hands. We are light-addicts, image-maniacs. We need breaks. Dead batteries. Black screens. Closed curtains. For new images to emerge.

In their film Reflection in a Dead diamond (2024) Hélène Cattet & Bruno Forzani play with the contrast between darkness and light, between the disappearance of the image and its appearance, creating a filmic chiaroscuro in which the oscuro repeatedly seeks to swallow the chiaro, and vice versa. In this highly dynamic 87 min. piece, the characters constantly fight in order to remain seen, or hidden, or to plunge their adversary into the abyss. All surfaces seem to be playing in favor of these confrontations. While hermetic rooms and dark matters – the most ubiquitous one being black leather – repeatedly threaten to absorb the necessary brightness it takes for images to live, light seizes as many shapes as it can whenever the opportunity presents itself. It glimpses on the ocean’s surface, sparkles inside a summer-drink, is reflected by mirrors of all sizes. And of course, it repeatedly gets captured by diamonds – these luxury goods for which bad things happen. Sharpening light into weapons. “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend”2„Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,“ as sung by Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1949), lyrics by Leo Robin, music by Jule Styne.. But when that girl is an assassin, diamonds cut, diamonds kill.

Like in their previous films – Amer (2009), The Strange Color of Your Body’s Tears (2013), Let the Corpses Tan (2017) – Cattet and Forzani play with visual and narrative conventions borrowed from eurospy films from the sixties and seventies. The plot revolves around a former spy, John D (Fabio Testi), plunging back into his past and the endless pursuit of the mysterious Serpentik. While the young John D. (Yanick Renier) is the typical fantasized secret agent – elegant, square jawed, always wearing a suit – Serpentik (alternatively played by Maria de Medeiros, Thi-Mai Nguyen, Céline Camara, Manon Beuchot, Sylvia Camarda and Barbara Hellemans) appears under multiple identities, most often concealed behind a body-hugging leather suit that reveals only her eyes. Diamonds, glitters, champagne, inventive weapons, advanced technology, masks, laser attacks and explosions fill up the screen and offer a full spectacle to the viewer, who, by being constantly distracted, is transported to the stylish setting of the Côte d’azur with its brazing sun and dreamy beaches.

Now whereas the classical spy-film would typically follow linear plot, showing the mastery of the agent over time with the final accomplishment of a given mission, Reflection in a Dead Diamond’s structure is “kaleidoscopic”3The directors have mentioned in interview to be inspired by the technique of “kaleidoscopic writing” as used by filmmaker Satoshi Kon.: the film unfolds not as a mission with a goal, but as an obsession with the past, fragmented like light dispersed by a diamond. Not only does time appear nonlinear, the images also frequently take shape while multiplying themselves, as if they were part of a living organism. It is hard in this case not to mention Deleuze’s concept of the “crystal image”, which describes the moment when the actual (the present) and the virtual (the past) merge in the image, blurring or becoming indistinguishable, as seen in Alain Resnais’ Last Summer in Marienbad (1961). Similar to the male protagonist (named “X” and played by Giorgio Albertazzi) in Renais’ film, John D. is haunted by his memory, or more precisely, by the indistinction between his memory and fantasy. And whether it’s a coincidence or not, the relapses of both characters into the past occur while they are at a hotel.

However, whereas in Deleuze’s words, “the entire Marienbad hotel is a pure crystal” 4Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Continuum, 1989), 74.– meaning that it is time itself, experienced through memory, that we encounter in its corridors, – the hotel in Reflection in a dead Diamond is not a container of memory but an arena for its collapse. The film’s structure is marked by relentless cuts (if my observations are correct, no shot lasts longer than five seconds), propelling us across a succession of inside and outside spaces: tunnels, bars, dark rooms, cliffs, beaches, and more. Whereas Renais uses the hotel as a setting that itself behaves like a “mental architecture”, making us viewers feel as though we’re floating in time, Cattet and Forzani present time as cut and shattered into multiple spaces. The actual and virtual do coexist, but in violent succession, via rapid montage and overlaps. Rather than being forced into a cerebral meditation like it is the case in Renais’ piece, we’re left with an experience of sensory excess, which aligns with Cattet and Forzani’s broader aim of conveying a visceral cinema.

The images cut (and bleed), but they also breathe. Close-ups on inhaling and exhaling mouths and noses, accompanied by amplified breath sounds, act as premeditations or reactions to what is following or what has just happened. Along with the numerous close-ups on sharp-gazed eyes, these facial expressions often serve as dialogs. Indeed, the characters barely talk to each other; they mostly communicate with their faces and bodies. And when they do talk, their words ironically mostly refer to haptics and gazings. “C’est moi qui t’ai à l’œil. Tu me touches encore, t’es mort” (I’m the one who’s got my eye on you. You touch me again, you’re dead), says la cantatrice (Kezia Quintal) to John D. while they are having dinner. Whereas “to have eyes on someone” could insinuate observation and desire, it implies in this case surveillance and predation. The eye doesn’t merely see; it touches, takes hold of the other. While uttering these words, la cantatrice wears a dress made out of small woven disks that at once work as mirrors and as recording engines. A metaphor for the eye. But whose metallic matter also bears the capacity of slitting. The gaze becomes a weapon, sharp, deadly.

It is interesting here to consider the role of women in classical spy films, such as in the Bond series. Typically cast as glamorous assistants or seductive enemies, these female figures tend to contribute to the visual spectacle all the while being narratively disposable. They exist, in Laura Mulvey’s terms, “as erotic objects for the characters within the screen story, and as erotic objects for the spectator within the auditorium, with a shifting tension between the looks on either side of the screen.” Their power lies in being seen rather than seeing. Think, for instance, of the female protagonists in Guy Hamilton’s Diamonds are Forever (1971). Whereas one of the women who Bond (Sean Connery) sensually interacts with abruptly disappears from the narrative after she’s thrown out of a window – and thereby out of the frame, the screen, the film – his other, more serious love interest, is constantly reminded of her vanity and “stupidity” (Bond himself calls her stupid when she fails to follow his plan). The female characters in Cattet & Forzani’s films subvert this logic. Although they hold attributes of the femme fatale, glamorous and sensual, they cease to be mere objects of contemplation. Instead, they have internalized the technology of looking and turned it into armament. They don’t merely inhabit the frame; they actively frame others.

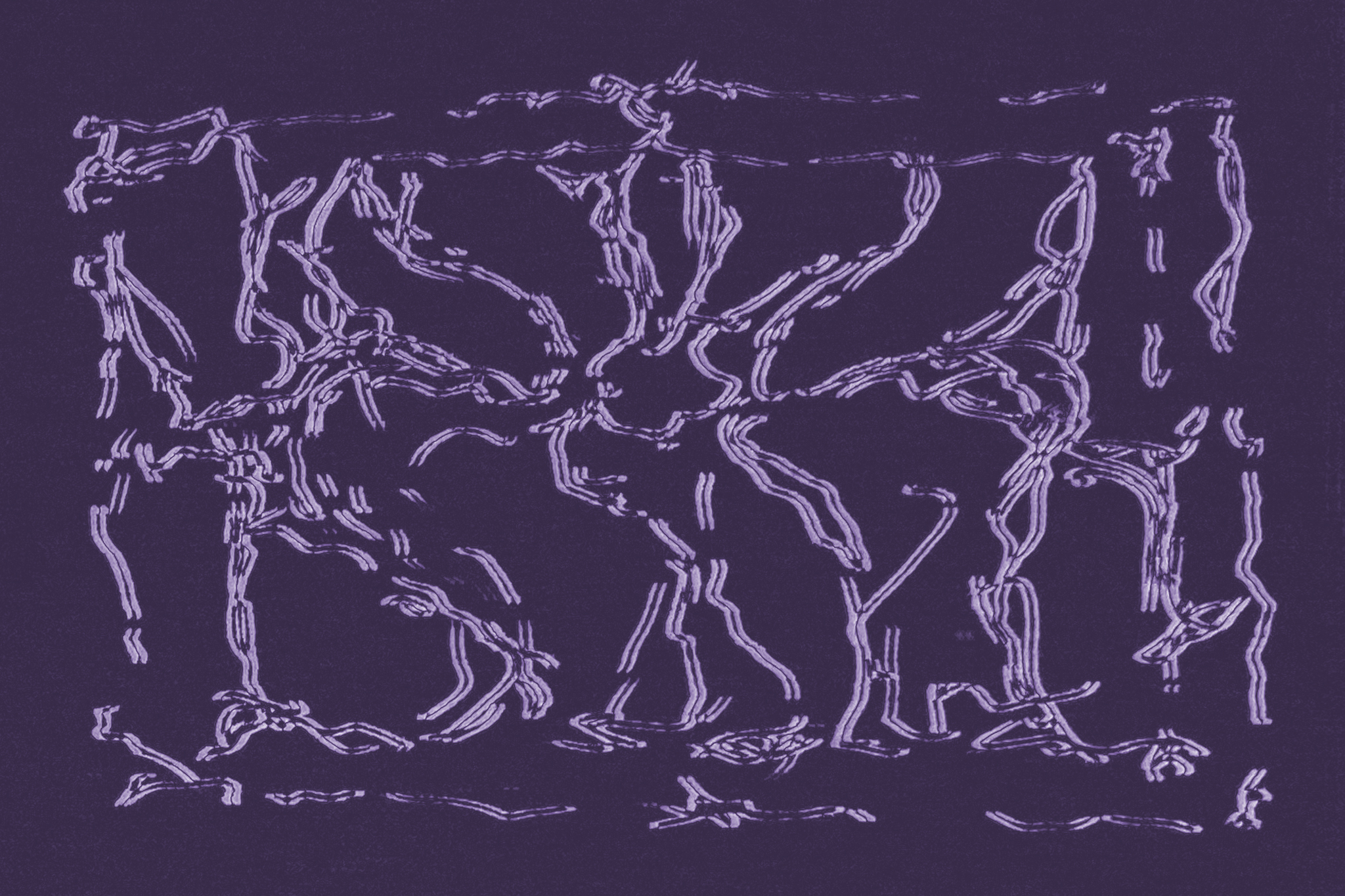

There is a scene, towards the end of the film, in which Serpentik confronts John D. in a battle. They’re in a black room, so dark that no border is visible. They seem to float in the infinite. Or inside the black box of a camera – the initial space of the image creation, where the visible is filtered and framed. At the start of the fight, their bodies emerge as autonomous forms, starkly contrasted against the darkness; they are figures made of light, images in motion. But they also appear as active agents within the process of the image creation. They are fighting to remain visible. As if they were two spermatozoids competing over a single place inside a womb. The battle ends when Serpentik envelopes her victim in her black leather suit. Covered by the light-absorbing fabric, he disappears in the darkness. Only his eyes remain uncovered but eventually, they vanish too.

Whereas Serpentik survives as an image, John D. does not. Does that mean that, released from his image, he actually accesses ultimate freedom, liberated from the world of appearances? Notable is that his disappearance actually occurs through his incarnation of the female figure. In fact, Serpentik’s leather suit functions as her second skin, at once concealing her identity and constituting it. When she covers him with her suit, her skin becomes his. However, whereas the leather suit has helped her cover her multiple identities by unifying them in one, it performs the opposite function for her adversary. Instead of gifting him the illusion of being complete, it strips him from his identity. In her skin, he does not survive. With her skin, she cheats and kills. And what is more efficient, for killing someone in a movie, than making them disappear in the depth of the black screen – into the very void from which images are born and into which they can so easily crumble?

The choice of casting Fabio Testi as the older John D. sharpens the theme of the image’s dissolution (and renewal) even further. Known for his roles in Italian genre cinema of the 1970s, Testi is the embodiment of the male archetype from a bygone cinematic era. His appearance adds a “vintage” flavor; but it also summons a memory of masculinity that was very reliant on cinematic and mediatic images. His presence, with his face carrying the weight of time, becomes the ghost of a cinema that believed in the solidity of its icons. Having him play the role of a retired spy as the narrative’s point of departure is therefore a perfect fit to highlight “the end of an era”. Still, the message is not delivered with resentment, but rather with amusement and appreciation with what that era had to offer, all the while contributing to the shift in its destiny. There are moments showcasing vengeance on the male body – the most obvious and effective one being a shot of literal castration – but these moments are handled with a peculiar humor, rendering violence absurd through its visual excess and the diegetic music loading them with a certain playfulness.

This interweaving of nostalgia and vision into the future is further enhanced by the combination of old and new filming techniques, blending 8mm, 16mm, and digital formats. The film thus honors cinema’s history while simultaneously recognizing its limits and opening its borders to new forms of expression. It does not attempt to restore the past, nor to break from it entirely, but instead lets memory and invention coexist within the frame. It lets the past splinter into multiple futures. Whereas *real* diamonds traditionally serve as promises of eternal love, *dead* diamonds kill the eternal. As mere reproductions of the real, they hold the benefit of mastering illusion. And what is cinema if it is not the careful weaving of illusion – a play of shadows pretending at permanence, a memory that knows it is a fiction?

Notes

- 1Renée Magritte in a radio interview with Jean Neyens (1965), cited in Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, trans. Richard Millen (New York: Harry N. Abrams), p. 172.

- 2„Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,“ as sung by Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1949), lyrics by Leo Robin, music by Jule Styne.

- 3The directors have mentioned in interview to be inspired by the technique of “kaleidoscopic writing” as used by filmmaker Satoshi Kon.

- 4Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Continuum, 1989), 74.